Here is my monthly column as it appeared Monday on 3QuarksDaily.

by Bill Murray

John Allen Chau, the missionary killed in the Andaman Islands in November, reopened the ‘uncontacted people’ debate. An advocacy group called Survival believes “Uncontacted peoples make a judgment that they are better off remaining uncontacted and independent, fending for themselves.” Most everybody else wants in, missionaries on their missions, doctors preventing disease, linguists to study imperiled languages.

Outside the Amazon basin most of the world’s uncontacted people live in New Guinea. The world’s second largest island is divided between Indonesia in the west where – as far as we know – all remaining uncontacted people live, and Papua New Guinea in the east.

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago. To be clear, we sailed up the Sepik River, in the north of the country, a region that has had contact with Europeans since their ships scouted the coast in the late 18th century. European settlers pressed indigenous labor into plantation work on the north coast from the late 19th and then, in the 1930s Australian gold prospectors trekked into the interior highlands and climbed out with eyes big as saucers, having made contact with nearly a million previously unknown highlanders. (Here is a remarkable video.)

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago. To be clear, we sailed up the Sepik River, in the north of the country, a region that has had contact with Europeans since their ships scouted the coast in the late 18th century. European settlers pressed indigenous labor into plantation work on the north coast from the late 19th and then, in the 1930s Australian gold prospectors trekked into the interior highlands and climbed out with eyes big as saucers, having made contact with nearly a million previously unknown highlanders. (Here is a remarkable video.)

Apprehensive but with faith in the civilizing force of the five or six intervening decades, our upper lips stiffened by the hotel minibar, we flew into the highland town of Mt. Hagen, gateway to the interior. Mt. Hagen comprised a single downtown street, a rugby field, airstrip, unkempt housing and not much more.

No tour groups clustered around leaders with flags; no backpackers struck poses of studied indifference. The police lived in barracks, prefab units half the length of a single-wide, where wives and children spilled onto verandas. I expect they’d have preferred thatch.

We shared a ride with a trader from Osaka to the Hotel Highlander, hidden behind a six-foot barricade. Men in yellow hard hats rolled back the high gate, color of a battleship. A fence surrounded the compound and more men in hard hats walked snarling black dogs around the inside perimeter.

The kitchen served dinner and stubbies, which is Aussie for short bottles of beer. Bony chicken is bony chicken, but they curled the tops of spring onions as garnish. A stab at flair.

•••••

A small plane carried us to the Sepik River. The pilot, already sweaty early in the morning in a tight short-sleeved shirt with epaulets, wielded a bathroom scale, weighed up his passengers (just my wife and me) and our gear, pulled a pencil from behind his ear and made the figures work on his clipboard.

A small plane carried us to the Sepik River. The pilot, already sweaty early in the morning in a tight short-sleeved shirt with epaulets, wielded a bathroom scale, weighed up his passengers (just my wife and me) and our gear, pulled a pencil from behind his ear and made the figures work on his clipboard.

He flew us to the river at Timbunke, worthy of a jot on the map but as far as I could tell, nothing more than a grass landing strip and six buildings. With road access north to Wewak on the Bismarck Sea, Timbunke was the last town with a road out the rest of the way upriver.

The entire Sepik River cruiser, the Sepik Spirit, was ours. Nobody but us, a crew of nine and captain Graeme, for three days. We climbed onto the third observation deck to view the daily thunderstorm over a savannah menaced by gathering nimbus and churned by sheets of shower.

The Sepik Spirit jammed up onto a sandy spit off Tambanum village and we clambered onto its stand-in shallow-draft landing craft, the proper one having gone clear to Karawari for repair. Every day they had fits trying to start its outboard motor.

The old beast juddered to a stop beside canoes carved from single trees, dragged onshore and parked perpendicular to the waterline. The son of Namba, the village elder, invited us into his father’s home.

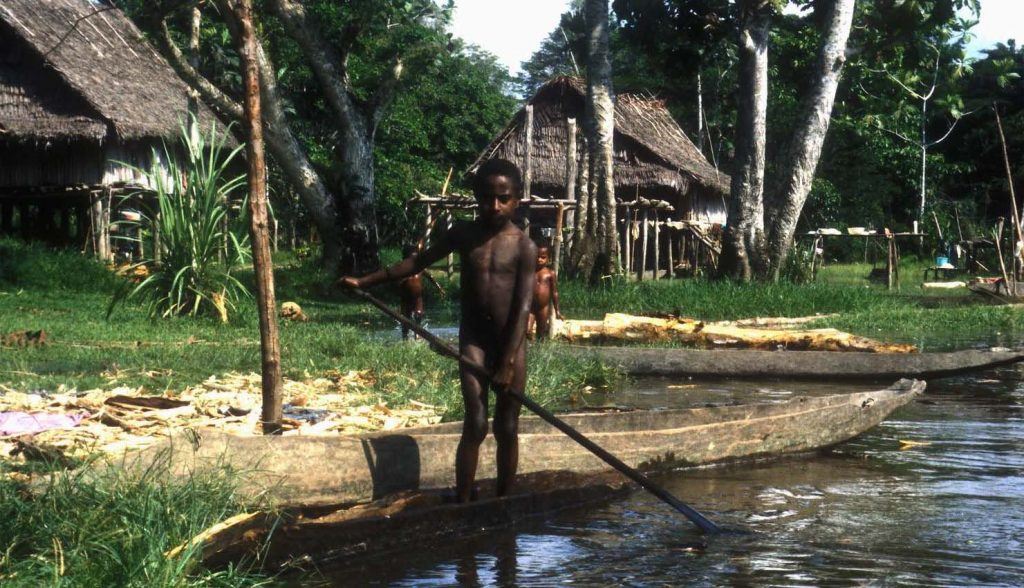

Typical Sepik River Village

All these houses of trees and vines stood higher than a person off the ground against animals, flooding and nat nats, or mosquitoes. The littlest baby, just three weeks old, slept under a mosquito net, one of not many concessions to the modern age. Seven poles lashed to two longer ones comprised the ladder to the door. Clay fire-pots allowed cooking inside. Drums, pots and baskets dangled from the rafters.

Tambanum was Catholic, having been converted by a missionary from down toward the mouth of the Sepik. A painting of Jesus hung at the top of Namba’s stairs. Below it was a traditional Sepik carving, in the shape of virgin and Son.

The elder Namba didn’t know how old he was. He had lived on the same patch of ground all his life. He said his father was bombed in this same place – just right there – by Japan. Namba’s son translated. His house, identical, stood directly behind Namba’s.

With a ceremonial fuss Namba brought out the family’s most prized possession, a bridal veil made of thousands of tiny nassa shells. I tried it on, too flippantly. We handed it around. Lawrence, our guide, went full reverential.

“It is byoo-tee-ful!” he murmured.

I suggested it took weeks to weave.

“Months.”

Namba walked us down to his front step and bid us farewell leaning heavily on his cane, wearing a tattered orange Brisbane Broncos T-shirt, ear lobes elongated by tribal tradition, smiling a broad smile ravaged by scarlet betel nut stains.

Ancient pipe-smoking women sat cross-legged along the path from Namba’s house, weaving baskets. A knot of men advised two others with Swiss-made metal tools and hand-carved mallets how to carve a table into the shape of a crocodile.

Two dugout canoes glided down the russet-colored Sepik as if on fire. When river folk caught a fish they smoked it in a clay pot right on the boat. The smoke kept away the nat nats.

Family in a dugout canoe on the Sepik River

•••••

Elsewhere by ritual you must come in, sit down, drink Pepsi, make small talk before negotiating can begin. Impecunious Tambanum got right down to business. When a boat tied up they produced a practiced mise en scène of artifacts. And came too quickly with their fallback position.

“How much?”

“Fifteen kina.”

“Second price twelve kina.”

They had no jobs for there were no jobs, 3000 people with no power, ice or medical care. They built their own houses and taught the arts of weaving and carving to their kids. Their food lived in the river and the trees.

We gave them their first price. That would be the village’s currency income for the day, maybe the week. It took a lot of hand-carved tourist masks for a village to save up for something useful like an outboard motor.

•••••

At twilight we’d sit on mats up front with Benny the pilot, watching cooking fires kick up lambent shorelight. Creatures of the night emerged from the forests; the sky darkened with no light from shore to chase it back. Inky sapphire settled over creation, and the deck would be thick as black snowfall with bugs in the morning. They’d sweep it clean.

At sunup, river glassy smooth, we crawled onto the landing craft, destination Angriman village. As soon as they were freed from the ship, the deck hands broke out the betel nut and turned full-animated.

The people of Angriman were the best crocodile hunters on the river. They raised them for their skin. When maybe four years old, a medium sized croc fourteen inches around might bring 200 kina from the Japanese agent who sailed in every three or four months. The biggest would bring 300. Fifteen or 20 three-footers lay about in a wooden stockade.

The croc stockade at Angriman

Each Sepik village selected a councilman. The Sepik Council met every other month or so, sometimes at Karawari, sometimes at Timbunke, and elected a representative to send to parliament.

Peter Mai, the Angriman councilman, greeted us. We gave him a postcard from where we lived, a place with skyscrapers. Four teenaged girls sang The Wonder of It All from a Seven Day Adventist hymnal, and then we stood in a receiving line as the congregants each shook our hands.

The Seventh Day Adventists got here first. Just sailed right up the Sepik winning converts. Now they were losing ground to the Catholics because they’d tried to banish traditional beliefs. They wouldn’t allow traditional dress.

Angriman produced watermelon, Malay apple trees, yams, mulberry bushes and a surplus of smoked fish. With more fruit and vegetables than it needed, crocodiles for sale for currency and fish in exportable quantity, Angriman prospered. But Angriman wasn’t served by a road and unfortunately, it was no longer on the river.

The Sepik changed course some years back leaving Angriman a literal backwater, off the main channel. Still, the crocodile trade yielded wealth: Evinrude outboard motors attached to longboats.

•••••

Upstream that night, anchored offshore, we peered into meager adumbrations of an unknown village. Some of the villagers owned kerosene lamps, but kerosene wasn’t to be used lightly. In the new day that village, Mindimbit, came to life as positively mercenary.

Mindimbit Village

One man had brought an immature cassowary, a blue-necked flightless, four-foot bird named Betty from Karawari. He charged a kina a camera for pictures. With the Sepik Spirit a sometimes visitor, Mindimbit was relatively grizzled at the artifact trade. Prices were higher.

Beside three Evinrudes and a Yamaha outboard in a shed of thatch, a frame of two-by-fours and four-by-fours stood unfinished. “They run out of money,” Lawrence explained. Planed wood is just not as practical as traditional houses lashed together with palms. With factory wood there was more to buy. Like nails.

A man named Wesley invited us into his house.

Up the stairs (watch your head!), three women cooked lunch and minded the kids, everybody on the floor. With a shower dancing on the roof, Miss Julie smoked a spatchcocked fish on a little round metal stove. Grandma minded a little boy, several cooking pots and plates of greens, and Wesley’s wife made sago pancakes.

To make the staple food you cut down a sago palm, drag it to the village, skin its bark, chop it into hunks, then smaller hunks, then pummel and pulverize it to pulp, and finally sluice it through banana leaves into a paste and dry to a powder.

Grinning a toothy grin, Wesley’s wife scooped the powder into a clay pot. A fire crackled underneath. With her cup she pressed it into pancakes. She’d press each into a foot-long oval and fold it in half. When it cooled we all tore edges off and popped them in our mouths. Captain Graeme said his wife added powdered coconut for a little flavor.

•••••

The sun would set in an hour and the river had smoothed for sunset. Benny smoked his hand-rolled faggots down to burn his fingers while steering through swamp and short grass. The forest rolled back to reveal mountains under cumulus.

We eased up along the north bank of the Sepik. Thatch imbricated a basic provisioning center where we sought curry, matches, tobacco and a Sydney Morning Herald dated March 28th. It was September. But this newspaper wasn’t for reading. It was rolling paper for the tobacco. Three broadsheets sold for fifteen toea.

Outside, imposing, voluble men loitered, but offered only friendly chews of betel nut, gesturing amused instructions. We split ‘em open and popped the nuts into our mouths. You chew, generating saliva, and spit the juice through your teeth, retaining the meat.

The juice is white. You dip a bit of mustard stalk into “lime,” pounded from mussel shell, and chomp it. It turns the juice bright red. Chew, spit, chew. It’s a little bitter and it gets your heart moving a bit, a little blood rushes to your head, everything’s a notch more intense, and then it fades. Think kava, Indonesian kratom or your first deep drag of nicotine.

Going for a swim from the old landing craft

After darkness spread full and complete, Mirja, Lawrence and I sat on rattan and cushions in the center of the Sepik Spirit. Insects threw up a wall of sound while canoes glided alongside silently. Adolescent boys peered in, cupping their faces to the windows.

Lawrence had a story to tell.

“Now I will tell you how our elders taught us the secrets of the spirits.

“I was fourteen. I was working since I was twelve, with westerners. I ate western food. I did not believe there were spirits.”

Still, at fourteen, there was room for doubt.

“It was frightening. We would start at six p.m. and they kept us awake until six in the morning. For days.

“They built a wall in front of the spirit house with a door too small to walk through. They lit the palm fronds over the door into a fire and told us to run as fast as we could and squeeze through that little door, and not to get burned by the falling ashes.

“My grandfather was the village leader so I had to go first. Five boys were behind me. I was scared but I ran fast as I could and I squeezed through that door and up the steps into the spirit house.”

The squeeze symbolized the return to the mother’s womb, because you must reunite with your mother’s spirit as a rite of passage before your father can teach you the spiritual secrets.

“Inside the spirit house, bad news! The men from the village were there and they were whipping us with canes to show us the power of each spirit. Ohhh, and it hurt!”

Lawrence grimaced and held his forehead. His eyes widened so that white showed clear around his pupils. He chewed a knuckle.

“And now it was late, about five in the morning. They gave each boy a betel nut. My grandfather told me the one he gave me was a special one. They told us to chew them, it would be good for us. We spit out the juice and kept the meat inside our mouths.

“They gave us pieces of ginger and told us to chew them. They played drums and these flutes at the same time. I felt like maybe I had a gin and tonic!

“I was dizzy and then I started seeing skeletons dancing and then I had these incredible dreams. And I believe in Jesus and Mary but since that night I have also known that spirits are real, too.

“We believe the father gives us the knowledge but the blood comes from the mother and so it must return to her. So my mother’s brother came from another village.

“The night of the skin cutting we stayed up all night. When it was very late the men made us go into the water and stay for one hour so our skin would get soft. Ohhh, it was so cold!”

Lawrence was sweaty as a bayou preacher. He massaged his temples and pulled his legs up on the sofa.

“When it was time I laid down on top of my mother’s brother. So the blood would fall on him. And they cut me.”

With a flourish he raised his right sleeve to show the results.

“Sometimes they cut your back but I asked they only cut my arms because I had to go back to work.”

He had to have time to heal.

But he didn’t heal. He was infected.

“I asked for medicine but my grandfather refused. He asked me, ‘What have you done wrong?’ I said nothing, nothing over and over but he kept asking me until finally I admitted I had stayed with my girlfriend the night before.

“Before they would use sharp bamboo leaves but now they use razors. I asked my grandfather if the razor was old but he said no it was bought new for this purpose. My infection was punishment for this bad act.”

His grandfather, who Lawrence called, “A famous headhunter,” told him at the end of his weeks of spiritual training that he would have unbelievable opportunities in the future. One of the people he had led on a cruise like this recently offered him a trip to the U.S., and to Lawrence, that was proof positive it was so.

More photos from Papua New Guinea at EarthPhotos.com.